The Whole Tooth

The History of the Toothbrush

Egyptian Toothpicks

Egyptians were perhaps the first to practice good oral hygiene over 5,000 years ago using a primitive form of the toothbrush. Even prior to this there is some evidence that the Mesopotamians used a primitive toothpick or ‘siwak’. These original toothpicks were most often made from porcupine quills, bird feathers, or wooden thorns. Eighteenth-and nineteenth-century Europeans elaborated slightly on the theme through the addition of silver and copper castings.

It’s interesting to note that the toothpick is still used as the primary tooth-cleaning mechanism by an estimated 10 million people in the Middle East and throughout the world. In fact, toothpicks were used as the primary method for cleaning teeth as late as the early 1950s in some isolated sections of the US.

The First Toothbrush

Throughout the seventeenth century, the preferred method among Europeans for cleaning one’s teeth involved the use of rags or sponges dipped in sulfur oil or a salt solution. The rags would then be rubbed against the teeth. Sometimes these rags were attached to a stick to help reach the back teeth, but the teeth were essentially being mopped, rather than brushed.

William Addis was the first to actually assemble a crude version of the modern toothbrush by attaching hairs from the tail of a cow to the end of a whittled bone. Eventually, boar hairs replaced cow hairs as the preferred bristle.

The Toothbrush Gets A Facelift

With the advent of plastic injection molding, celluloid handles soon came to replace conventional bone handles. The concurrent nutritional demands of WW I also played a role in driving the change. The next major change came late in the 1920s, a new method of attaching bristles to the handle was developed: drilling holes into the brush head, forcing in bunches of bristles, and securing them with a staple. In fact, this method is still used by a few manufacturers. Prior to World War II, Chinese boar hairs were the favored material for bristles. Manufacturers switched to the newly developed nylon filament after a roadblock out of Chung-King impeded the export of these popular hairs.

The nylon filament came with several advantages, including a dramatic reduction in production costs and the ability to control bristle texture. Manufacturers could also shape the filament tip and vary its diameter for improved performance. Boar hair, on the other hand, often fell out, did not dry well, and was prone to bacterial growth. Although nylon continues to dominate the market today, boar-hair bristles still account for about 10 percent of toothbrushes sold worldwide.

Today’s Toothbrush

In the last 20 years, there have been about 4,000 toothbrush related patents; the brands, styles and colors of which are virtually endless.

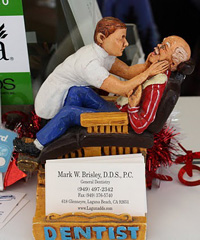

Come on down and visit Dr. Brisley’s office where we have a toothbrush for you. Keep Smiling!